The Battle for The Rocks - 50th Anniversary

The Rocks was the site of Australia's first European settlement in 1788. As the preface to Australia's story, The Rocks played stage to the colony's first residential neighbourhood, along with the initial bakehouse, hospital, and pub. Social historians see The Rocks as more than just the starting point of modern Australian history; they see it as the cradle of the nation’s identity.

Inextricable from this history are the lives of the working-class people who lived here for generations. These families, known as 'battlers,' consisted mainly of dockworkers, factory workers and maritime professionals. These communities were the very essence of The Rocks, something that no development could manufacture. They were also prepared to fiercely resist the proposed demolition of their homes in a series of events that would come to be called 'The Battle for The Rocks.'

A New Plan for The Rocks

In the 1960s, Sydney experienced rapid commercial growth under Premier Askin. With its proximity to the CBD and public ownership, The Rocks quickly captured the government's interest. In 1970, the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) was established to implement a $500 million redevelopment scheme, equivalent to $6.5 billion today, to replace The Rocks with office blocks, hotels, and more.

Illustrating the disregard for public sentiment during this period, G.J. Dusseldorp, then chairman of Lendlease, remarked to a group of housing leaders that the industry couldn’t ‘care less’ about people’s desires. Premier Askin labelled The Rocks as a ‘depressing’ area.

Swiftly authorised without public consultation, the plan for The Rocks triggered outrage, leading to the formation of the Rocks Residents Action Group (RRAG) led by Nita McRae. After a year of futile petitions, RRAG sought help from the NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF), who placed a green ban on The Rocks in 1971.

The Green Bans

The NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF), led by Jack Mundey, Joe Owens, and Bob Pringle, was the first worldwide to introduce the concept of Green Bans. They sought a new form of unionism that gave workers the right to refuse participation in projects considered harmful. The bans targeted projects encroaching on public green spaces, demolishing existing public housing, or replacing historic structures with modern buildings. Mundey emphasised the importance of environmentally conscious designs. The first green ban was placed on Kelly’s Bush in 1971, which sparked a wave of similar appeals to the BLF.

A People's Plan

The fight for The Rocks was distinct from Kelly's Bush as it involved a state authority, not a private developer, and centred on housing and welfare for low-income tenants.

The green ban gave The Rocks Resident Action Group time to strategise and formulate their own counterproposal to the SCRA Scheme. Collaborating with architects like Neville Gruzman, they established The Rocks People’s Plan Committee and crafted a ‘people’s plan.’ Their goal was to keep safeguard The Rocks as a residential and historically significant area.

Nita McRae

The Wrecking Ball

In August 1973, SCRA announced plans for a $1 million low-rise apartment block on Playfair Street. The site was already home to Playfair’s Garage, an industrial gem from the 20th century. Owen Magee, SCRA’s director, dismissed the site as having no value. Nita McRae and the RRAG quickly mobilised the BLF and other activist groups.

It's worth noting that while the movement’s leaders were keen on heritage preservation—the BLF refused to demolish any of the 1,700 buildings in NSW that were recommended for conservation by the National Trust—their chief focus was on protecting social and urban rights for the area's working-class residents.

Jack Mundey made it clear that the green ban would only lift when residents were satisfied with the plan. However, non-union labour had begun demolishing the building. It was time to act.

The Battle Unfolds

Thursday, 18 October 1973

The BLF effectively brought demolition to a standstill by staging a protest that saw over 100 workers leave their job sites. At first, the contractors snubbed the BLF's ban but later consented to a 24-hour truce for negotiations. Expecting that demolition might resume, representatives from seven different sites across the city agreed to keep an eye on the Playfair Street situation. Should the demolition go ahead, the BLF was prepared to occupy the area.

Friday, 19 October 1973

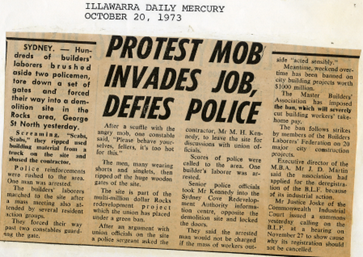

Demolition continued. Labourers protested the breach of the ban at the Playfair Site and the SCRA offices. Joe Owens warned that if demolition proceeded as scheduled on Monday, the site would be occupied once more. Owen Magee, the SCRA director, gave his assurance that no further work would take place. However, he later accused BLF of inciting violence and said he would not concede.

Monday, 22 October 1973

At 8:30 a.m. Monday, Owens learned SCRA halted work due to occupation threat. If bans were violated again, they agreed to regroup. Owens and Pringle met the state opposition leader, urging a comprehensive strategy for preserving historic areas as low-cost housing in the Labour Party's policy.

Tuesday, 23 October 1973

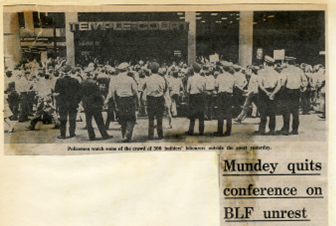

Mr Justice Aird presided over a Conciliation Commission conference on Tuesday. Sixteen members of the Federation's Federal Executive, along with a representative from the Master Builders Association (MBA), were called to attend. The Commission implied the threat of deregistration if the Green Ban on The Rocks wasn't lifted. However, Jack Mundey opposed conducting the meeting without state body or local resident representation, asserting that the BLF wouldn't be strong-armed into compliance.

Wednesday, 24 October 1973

By the first light of dawn, a diverse ensemble of approximately 100 individuals began assembling at the Playfair Street site. Comprising union executives, students, and members of resident action groups from The Rocks, Woolloomooloo, and Kings Cross, they were equipped for a day-long peaceful occupation with food, beverages, radios, and musical instruments. To secure their position, they improvised barricades using oil barrels, corrugated iron sheets, and hoses.

As 7 a.m. approached, the first of the law enforcement agents began to arrive. By 8 a.m., a contingent of 60 police officers armed with tear gas began dismantling the makeshift encampment. The crowd, though physically dispersed, maintained a vocal presence, chanting "Keep The Rocks for the people!" as they were systematically and forcibly removed.

The tense standoff concluded around 7:30 p.m. when the last protester was apprehended. Sequestered in a tree for nearly nine hours, this individual identified himself to the police as Elvis. 54 demonstrators—including BLF leaders Jack Mundey, Joe Owens, and Bob Pringle—were charged with trespassing. An image of Mundey with clasped hands and an unfazed expression as he was casually escorted by three policemen became the iconic photo of the movement.

Thursday, 25 October 1973

Undeterred by the previous day's setbacks, protesters reconvened at First Fleet Park. After speeches by Bob Pringle and Jack Mundey, the crowd marched with arms linked and voices raised in a unified chant of "green bans, Askin out." They set off on a spirited march up Pitt and Hunter Streets to demand an audience with Premier Askin. A seven-piece jazz band provided a rousing soundtrack as they marched behind a banner that read "B.L. (Builders Labourers) Care for People."

Upon arrival, they were met with a wall of furious police officers blocking the entrance to the building. After a heated exchange, they were told that the Premier was on holiday.

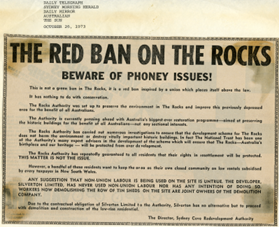

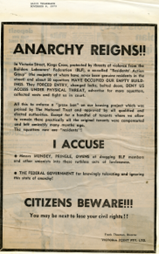

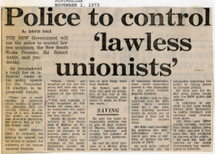

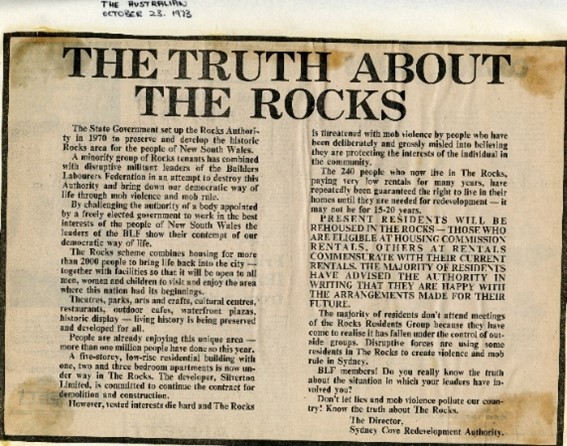

Media Response

Despite SCRA promises, 'scab' labourers repeatedly occupied sites. For two weeks, the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) faced relentless opposition from law enforcement, despite their best efforts to keep interactions peaceful.

The media was quick to cast the protesters as violent and their efforts futile. SCRA ads accused the union of lawlessness and residents of wanting exclusivity at taxpayer’s expense. Premier Askin labelled union leaders as 'extremists.'

Despite the negative portrayals, support for the protesters swelled from other unions and the public. Attempts to tarnish their reputation were increasingly seen as ineffective and attempts at bribery were flatly rejected. Slowly but surely, the tide of public opinion started to turn in their favour.

The Triumph of Resilience

Perhaps sensing the changing winds and with $5 billion worth of development being held up by the ban, SCRA capitulated. They began to emphasise their efforts to restore historically significant buildings and agreed to allow residents to remain at housing commission rates. One journalist quipped that the Builders Labourers Federation had become the most powerful town planning agency in New South Wales.

From High-Rise Ambitions to Heritage Priorities

The battle for The Rocks transformed urban planning in 1974, leading the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) to reconsider their approach. They limited skyscrapers to south of the Cahill Expressway, preserving the area's heritage to the north. Notably, Playfair's Garage was saved from demolition. The SCRA's commitment to the residents extended to the construction of the Sirius apartment building in the late 1970s.

The green bans' success led to laws like Environmental Protection Act 1974 and New South Wales Heritage Act 1977, setting conservation standards. Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 and Land and Environment Court Act 1979 established checks against irresponsible developments.

In 1998, when the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority took over the reins, it inherited this evolved approach to planning. Preserving the essence of community-driven ethos, their work extended to archaeological explorations that unearthed facets of colonial history. Today, The Rocks is a vibrant cultural hub, adorned with public art, including a towering portrait of Jack Mundey on Globe Street. The Rocks Discovery Museum showcases the green bans' legacy through exhibits that illuminate the movement's stories and struggles.

The Sirius building on Cumberland Street

A Lasting Legacy

The direct action by residents and union members led to The Rocks earning conservation area status, complete with over 100 heritage-listed items. This landmark accomplishment set the stage for culturally relevant development. The intact buildings, public areas, and parklands in The Rocks stand as concrete evidence of the Battle for The Rocks.

Reflecting on the pivotal events of 24 October 1973, Mundey noted how collective actions like the occupation empowered citizens, halting insensitive developments, and involving the public in decision-making.

Today, The Rocks serves as a compelling testament to the power of working-class action. It's a constant reminder that urban development must be balanced with a deep respect for history and community. As we commemorate its 50th anniversary, it's an opportune moment to reflect not just on the dedication of those involved but also on what we, as a society, should prioritise for preservation and continued advocacy in the decades ahead.

.png)

The famous image of Jack Mundey’s arrest installed on a plaque on a section of Argyle Street, renamed Jack Mundey Place