08 Oct 2025

Meeliyawul: The Deep History of The Rocks

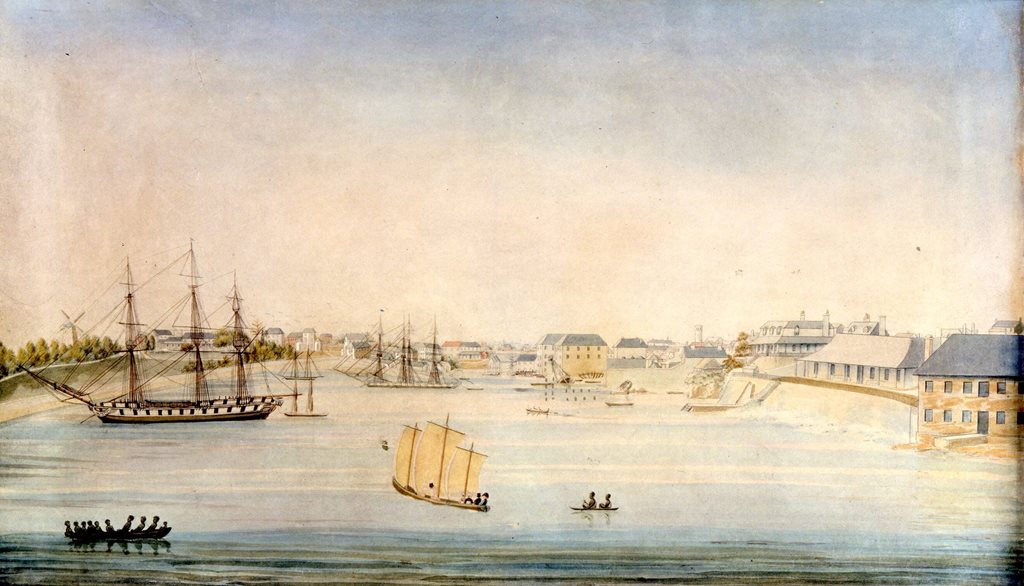

The Rocks is often described as Sydney’s birthplace, but its history runs much deeper than European settlement. For thousands of years, the Gadigal people lived on this land, fishing, gathering, and moving along pathways that connected the harbour to what we now know as George Street.

From Gadigal Pathways to Bethel Street

In the 1860s, an original Gadigal pathway between two rocky outcrops was widened into a thoroughfare known as Bethel Street, linking George Street with the waterfront. But recent discoveries reveal its origins stretch back much further.

In the 2010s, researchers uncovered a rare map hidden among Admiralty papers in the British National Archives. Dated to the very first months of British settlement, the map identifies the track that became Bethel Street, suggesting it was not only one of the earliest colonial “roads,” but almost certainly a much older Gadigal pathway.

Some scholars now believe this location—once marked on early maps as “Reed’s Rocks”—was where the First Fleet first came ashore.

In the 2010s, researchers uncovered a rare map hidden among Admiralty papers in the British National Archives. Dated to the very first months of British settlement, the map identifies the track that became Bethel Street, suggesting it was not only one of the earliest colonial “roads,” but almost certainly a much older Gadigal pathway.

Some scholars now believe this location—once marked on early maps as “Reed’s Rocks”—was where the First Fleet first came ashore.

Meeliyawul and the Harbour Shoreline

The shoreline here once looked very different. In the 1840s, two rocky outcrops were levelled to make way for Circular Quay. These rocks had collected sand washed down from The Rocks, creating a small natural beach in contrast to Sydney Cove’s rocky edges and the mudflats near the Tank Stream.

It’s likely that the Gadigal name “Meeliyawul,” recorded in 1790–91, refers to this very place—a reminder that Sydney’s earliest stories are embedded in language as well as landscape.

It’s likely that the Gadigal name “Meeliyawul,” recorded in 1790–91, refers to this very place—a reminder that Sydney’s earliest stories are embedded in language as well as landscape.

Traces Beneath the Sandstone

As The Rocks developed through the 19th century, sandstone was quarried, houses and warehouses were built, and many early traces of Aboriginal occupation were erased. Yet archaeology continues to reveal glimpses of life here before and after European settlement.

Excavations at Cumberland Street’s “Big Dig” in 1994 uncovered quarrying scars that reshaped the land, while at the Lilyvale site in 1989, archaeologists found the remains of a 500-year-old Aboriginal campfire—oyster shells, bream, and snapper cooked and eaten while overlooking the harbour.

Excavations at Cumberland Street’s “Big Dig” in 1994 uncovered quarrying scars that reshaped the land, while at the Lilyvale site in 1989, archaeologists found the remains of a 500-year-old Aboriginal campfire—oyster shells, bream, and snapper cooked and eaten while overlooking the harbour.

Shared Lives, Shared Struggles

Aboriginal people continued to live, work, and form relationships in The Rocks throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Figures like Billygong worked closely with colonial landowners such as Alexander Berry, while oral histories and records continue to uncover stories of resilience and adaptation in the heart of the growing city.

On the waterfront, Aboriginal wharf labourers became part of Sydney’s working-class fabric. Leaders like Fred Maynard, who founded the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924, were influenced by civil rights movements abroad and carried those ideas onto Sydney’s wharves. Later, community leaders such as Charles (Chicka) Dixon, Herbert Charles Grant, Patrick Freeman, Percy Natty, Leslie Brindle, Jack Hassen, and Ray Peckham became powerful advocates for Aboriginal rights and social justice.

Supported by strong alliances with trade unions—similar to the Green Bans of the 1970s—Aboriginal workers and activists challenged unjust evictions and campaigned for a more equal society.

On the waterfront, Aboriginal wharf labourers became part of Sydney’s working-class fabric. Leaders like Fred Maynard, who founded the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924, were influenced by civil rights movements abroad and carried those ideas onto Sydney’s wharves. Later, community leaders such as Charles (Chicka) Dixon, Herbert Charles Grant, Patrick Freeman, Percy Natty, Leslie Brindle, Jack Hassen, and Ray Peckham became powerful advocates for Aboriginal rights and social justice.

Supported by strong alliances with trade unions—similar to the Green Bans of the 1970s—Aboriginal workers and activists challenged unjust evictions and campaigned for a more equal society.

From Meeliyawul to Bethel Street, from Gadigal pathways to union activism, The Rocks holds layers of history that continue to shape Sydney’s identity. It is a place of resilience, reinvention, and community—where ancient traditions, colonial upheaval, and modern activism meet.

Stay up to date

Get the best of The Rocks straight to your inbox.